Introduction to Python¶

In this chapter 1, we will examine the basic facilities of the Python programming language, and go on to the more advanced features in the next.

Characteristics of Python¶

Here is a high-level look at the features of Python, for those with a background in programming languages.

Scripting¶

Python is a scripting language. This loosely means that you do not have to compile Python programs; Python can execute them directly. In fact, you can type lines directly into the Python interpreter and have it execute them interactively. Python does compile programs into code it interprets, but it will handle the compilation itself, without troubling you.

Nondeclarative¶

Python programs consist of executable statements. They don’t have declarations. In most languages, you declare a function; in Python, you execute a statement that creates a function object and assigns it to a variable. In other languages, you call a function by giving its name and an argument list. The Python call looks exactly the same, but instead of the name of the function, you specify the name of the variable containing the function as its value.

Typeless or dynamically typed language¶

That means that variables do not have static (declared)types; values have types. Variables are not declared. A value of any type may be assigned to any variable.

High-Level¶

Python is a high-level language. It has high-level data structures built into the language, such as dictionaries that allow you to associate values with objects. Python has had a garbage collector. You allocate objects whenever you need them, but you don’t have to delete them. When there is no way left for the program to access the object, when there are no pointers left that point to it, Python automatically frees its storage. Older versions of Python also deallocate objects automatically with a reference count scheme, which will not reclaim storage of circularly linked, inaccessible structures.

Modular¶

Python programs are organized as collections of modules kept in libraries. Each module is kept in a separate file, and the libraries in directories. A good programming practice, when writing larger programs, is to use as many preexisting modules as possible and to divide the code you do write into general-purpose modules. These modules can be debugged individually and can be reused in other programs.

Object-Oriented¶

Python has facilities that allow object-oriented programming. It has classes and inheritance, as any proper object-oriented programming language should. But Python is not perfectly object oriented. Python does not provide private or otherwise restricted scopes for names. The information-hiding aspects of object-oriented programming are on the honor system.

With Operator Declarations¶

Python allows you to create functions for the built-in operators, to be used when the operators are applied to instances of certain classes. This allows you to implement abstract data types, new types of objects with their own set of operators. The operators include subscripting operators, so you can implement new types of objects that behave like arrays.

With Metaprogramming Facilities¶

What Python calls metaprogramming, other languages refer to as introspection or reflection. The program itself can examine and modify its interpreter’s own state and components while it is running. This is useful for debugging and for changing the running program under program control.

Executing Programs¶

Interactive Use¶

You can execute Python from the command line in a command window. It

will come up with a greeting and a command prompt (>>>). 2

$ python

Python 3.6.5 (default, Apr 1 2018, 05:46:30)

[GCC 7.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

You type Python statements at the command prompt, and Python executes them immediately. If you type an expression, Python will evaluate it and type out the value.

>>> 12+14+20

46

We will use the command interpreter to try out Python features to show how they work.

Python statements can extend beyond the end of a line, in which case the

interpreter will give a different prompt (...) for the continuation:

>>> (1+2

... )*3

9

Python can’t always figure out that you wish to continue a statement to another line. The way you force it to continue to the next line is to put a backslash, \, as the last character on a line. This is customary in Unix-like systems. It incorporates the following character, the newline, into the current line as white space.

Scripts in Files¶

You can also place programs in files and execute them from there. For example, you can edit a file SayHi in the current directory, containing:

#!/usr/bin/env python

print("Hello")

Then set SayHi’s execute permissions and execute it:

chmod a+x SayHi.py

$./SayHi.py

Hello

You can also run the script explicitly with Python:

$ python3 SayHi.py

Hello

#!/usr/bin/env python is a comment to the shell, the command interpreter on Linux. It tells

the shell that the way to execute this file is to execute the program in

file /usr/bin/python , and pass it the rest of the file as its

input. The print statement tells Python to write out the string Hello on

the standard output, which will write it to you. The print is

required when Python is executing a script in a file. When you are

typing directly to it, Python knows to write out the values of

expressions, but when it is executing scripts, it assumes you do not

want the value of every expression you execute cluttering up your

output, so it will not write out the values of expressions.

Arithmetic Expressions¶

Arithmetic Types¶

Python has four built-in arithmetic data types:

fixed sized (at least 32-bit) signed integers

variably sized, unbounded precision signed integers

floating point approximations to real numbers

complex numbers (with real and imaginary parts) for engineering calculations. We will not consider complex numbers further, since they are not typically relevant to Web enterprise applications.

Integer literals can be written in decimal, octal, or hexadecimal (base 16) format using the same syntax as in C or C++:

Octal integers begin with 0o (yes, it’s weird but true) and contain only octal digits (0-7).

Decimal integers begin with a decimal digit other than zero and contain only decimal digits.

Hexadecimal integers begin with 0x or 0X. The prefix is followed by a string of hexadecimal digits, 0-9, a-f, A-F. The letters A, B, …F, of course, represent the values, 10, 11, …15.

>>> 20

20

>>> 0o20

16

>>> 0x20

32

Python (as of version 3) no longer distinguishes between integer and long integer,

which is a result of PEP 237. Integers are

always <class 'int'>. They are automatically widened to support any needed level of

precision. The following shows every 16 powers of 2 starting from 0.

>>> for i in range(0, 129, 16):

... print( i, 2**i, type(2**i) )

...

0 1 <class 'int'>

16 65536 <class 'int'>

32 4294967296 <class 'int'>

48 281474976710656 <class 'int'>

64 18446744073709551616 <class 'int'>

80 1208925819614629174706176 <class 'int'>

96 79228162514264337593543950336 <class 'int'>

112 5192296858534827628530496329220096 <class 'int'>

128 340282366920938463463374607431768211456 <class 'int'>

Since integers occupy single machine words, computers perform integer arithmetic very fast. Long integer arithmetic typically requires much more time. Therefore, you should exercise care when taking advantage of higher precision as it will affect performance.

Floating point numbers are written with a decimal point or an exponent,

or both. For example: .2, 2.0, 20., 2000e-1, 2E3.

Python allows mixed-mode arithmetic, as we saw above with 2L**32. If

the two operands of an arithmetic operator have different types, Python

will convert them to a common type. Python converts the operand whose

type has the smaller range of values to the type of the operand with the

wider range of values. (This is called a widening coercion: The

“narrower” operand is forced to be the type of the wider.) So, if they

are mixed in expressions, integers will be converted to long integers or

floats, and long integers will be converted to floats. The conversions

to float may lose some low-order digits.

Tables Operators and Precedence and Operators and Precedence (Continued) show a complete list of Python operators and their precedence levels. Some of the operators won’t be discussed until later sections; we’ll refer to the table then. The operators with higher precedence levels are performed before those with lower precedence.

The arithmetic operators in Python are much the same as those in C or C++. They are at precedence levels 9 through 12. The bit-wise operators (ANDs, ORs, shifts) are mostly at levels 5 through 8. Since they are not used much in Web enterprise applications, we won’t discuss them further.

We will discuss the logical and comparison operators later when we

discuss while loops.

Precedence |

Operator(s) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

1 |

|

This is the logical OR operation. It will return true if either |

2 |

|

This is the logical AND operation. It will return true if both |

3 |

|

This is the logical NOT operator. It returns 1 if |

4 |

|

Testing for equality, |

4 |

|

Operators |

5 |

|

This is the bitwise OR operation, ORing the XORing the corresponding bits in two integers. |

6 |

|

This is the bitwise EXCLUSIVE-OR (XOR) operation, XORing the corresponding bits in two integers. |

7 |

|

This is the bitwise AND operation, ANDing the corresponding bits in two integers. |

8 |

|

These are the shift operators. They apply to integers or long integers. The bits in |

10 |

|

Multiplication, division, and modulus (or remainder). Operator |

11 |

|

Negation, bitwise complement, and unary plus (no operation for numbers). |

Precedence |

Operator(s) |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

12 |

|

Exponentiation, \(x^y\) |

13 |

|

Function call |

13 |

|

attribute access |

13 |

|

subscripting |

13 |

|

slicing |

14 |

|

construct tuple |

14 |

|

construct list |

14 |

|

construct dictionary |

14 |

|

construct string |

Built-in Arithmetic Functions¶

Python has a number of built-in Mathematical Functions you can call. Other

mathematical functions can be found in module math. Complex

arithmetic functions are in module cmath.

Function |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

the absolute value of |

|

ompares |

|

Determines the common type for |

|

are integers or long integers, it assigns |

|

the value of |

|

the value of |

|

the value of |

|

Converts |

|

Assigns |

|

Assigns |

|

Assigns v the value of |

|

Assigns v the value of |

|

Assigns v the the floating point number |

Assignments and Variables¶

Variables are not declared. You create a variable simply by assigning a value to it. The simplest form of an assignment is:

variable = expression

For example

>>> a=10

>>> a

10

>>> b=a+2

>>> b

12

Variable names and other identifiers in Python are composed of letters, digits, and underscore characters. The first character of the identifier must not be a digit. The letters are the ISO-Latin characters A-Z and a-z. 3

You can also do several assignments on the same line; for example let’s

swap the values of a and b :

>>> a,b

(10, 12)

>>> a,b = b,a

>>> a,b

(12, 10)

We will look at this again later. Note also that we can list more than one expression on a line in interactive mode and Python will write out all their values. Both the multiple assignments and the multiple values on a line use tuples, a kind of sequence which we will discuss in Tuples.

Creating Functions¶

You may create a function and assign it to a variable with the def

statement, for example:

>>> def diff(x,y):

... return abs(x-y)

...

>>> diff(-10, 5)

15

creates a function diff that returns the absolute difference between

values x and y. There are several things to note about this

function creation:

The

defline introduces the code for the function. It gives the name we will call the function,diff, and the argument list. The function will be called with two arguments,xandy. Thedefline is terminated with a colon.The name

diffis not exactly the name of the function. It is a variable that is assigned the function as a value. It is an assignment as much as assigningdiff=valuewould be, and indeed,diffcan be reassigned.The body of the function is indented. All statements in the same group of statements must be indented the same amount. Soon we’ll look at

whilestatements, whose bodies must be indented beneath thewhile.The function returns a value with a

returnstatement.If there is no

returnstatement, the function does not return a value, and the call of the function should be used only as a statement, not within an expression.A function is called by the form

f(args)wherefis a variable containing the function andargsare the arguments being passed in.

When you use a variable name in a function, Python will look in three places to try to find what it means:

The function’s local variables. The arguments are already placed there; other variables assigned values in the function are also placed there.

The module variables. These are the variables assigned values in the interactive session or in the file that Python is executing.

The built-in names in the Python system. For example, the function

abs()is a built-in name in Python.

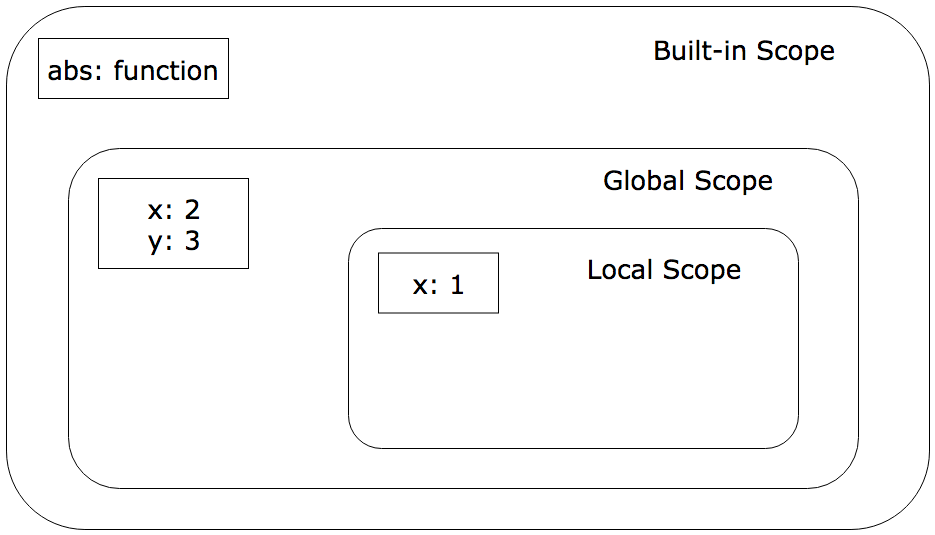

Figure 1 Understanding Python scopes¶

Figure Understanding Python scopes shows how Python searches scopes

for names. The search for a name starts in the

innermost scope and proceeds outward until the name is found or until

there are no more scopes. To find the name referenced in a function, at

most three scopes will be searched. When a variable is assigned a value

in a function, its name will be placed in the local scope if it is not

already there. For example, in if the function looks up the value of

x , it will get 1, the value of variable x in the function

itself. The variable x with a value 2 is in the global scope and is

hidden by the local x. If the function tries to look up y , it

won’t find it in the local scope, but will find it in the module scope

with a value 3.

Modules¶

As we discussed in Scripts in Files, you can put Python programs in files and execute them. However, the primary reason to put Python programs in files is to allow other Python programs to import and use the functions. A Python program that is used by other Python programs is called a module.

The way you access a module is by the import statement:

import moduleName

The import statement sees if the module has already been imported.

If it hasn’t been imported yet, Python finds the file that contains the

module. It will have the name moduleName.py, and will be found in

one directory in a list of directories (path). Python’s built-in library

of modules is on the path, so you can use all the modules in Python’s

library without difficulty.

Whether or not the module gets loaded, the import statement assigns

a module object to a variable in the local scope that has the same name

as the module, i.e., it behaves the same way as an assignment statement.

So

import moduleName

behaves like

moduleName = moduleObject

When Python loads a module, Python reads in the module’s file executing the commands. The commands assign values to variables within the module’s namespace that it puts the names in. These are available in the module object, so you can access the names defined in the module by the expression

moduleName.variable

For example, the module string has a built-in function atof() to

convert strings to floating point numbers. It also has a string variable

hexdigits that contains all the hexadecimal digits. So,

>>> import string

>>> string.atof

built-in function

>>> string.atof("314e-2")

3.14

>>> string.hexdigits

'0123456789abcdefABCDEF'

If you wanted to refer to the function by its own name directly, rather than prefixed by the module name, you could assign it to a local variable with the same name

>>> atof=string.atof

>>> atof(``314e-2'')

3.14

or you could just import the names you want from the module:

>>> from string import atof, hexdigits

>>> hexdigits

`0123456789abcdefABCDEF'

If you are using an interactive session to debug modules, you will have

to reload the module after every change. You reload a module using the

built-in reload() function:

>>> reload(moduleObject)

This will look up, load, and initialize the module. The new definitions

of variables within the module will override the previous definitions.

The module object will be changed in place, so all parts of the program

that have variables pointing to that module (i.e., all that have

imported it) will see the new definitions when referencing its

attributes through the module name, moduleName.variable.

However, there are problems that may force you to start a new

interactive session. If you use the from-import statement,

from moduleName import name

will have been done when the from-import statement was executed and

name will have the value of moduleName.name at that time. It

won’t automatically be updated. After reloading moduleName , you

will have to execute the from-import again to have the new value of

the attribute assigned to name. If names from module A are

imported into module B and you change module A , you will need

to reload module A to get the new definitions and then reload module

B to assign the new definitions to local names. This can quickly get

confusing.

Python provides the ability to import modules and assign them to variables with different names (i.e., not the name of the module), or import functions, classes, and variables from modules assigning them to local variables with different names. The syntax is

import module as name

from module import name1 as name2

Files¶

As with all programming languages, Python allows you to read and write

files. Python uses file objects for the operations. You create a file

object by calling the built-in function open()

f = open(name, mode)

where the name string gives a path to the file and the mode

string indicates whether the file is to be read from or to be written.

The mode is a string. Here’s a list of the modes:

'r': Open for reading. This is the default.'w': Open for writing. This will replace a current file with the same name.'a': Open for appending. Data will be added to the end of a currently existing file.'r+': Open for both reading and writing.

You may omit the mode parameter if you are opening the file for

reading.

File objects have methods for reading and writing and other operations. A method is a function attached to the object. The method has a syntax that differs a bit from regular functions. The object the method operates on precedes the function call, separated by a dot:

object.function(args)

This syntax has a couple of virtues:

It makes clear which object the method is operating on. Otherwise, the object would have to be one of the arguments, and you couldn’t be sure which.

It allows different kinds of objects to have methods with the same name; the system can find the correct one for the object. Many objects have similar operations. It would be a pain to have to invent different names for those operations, or to have to keep changing a single function to test what kind of object it has been given and execute some specific code for it.

There are three methods you especially need to know for files:

Reads the next line from a text file and returns it in a string. The string ends with the line termination character or characters, on Linux the newline character

'\n'. Empty lines thus consist of a single newline character. On end of file,readline()returns an empty string,".Writes a string to the file. The

stringis not made into a line, i.e., the newline character is not appended. If you want it, you will have to write it yourself.Finishes processing the file, either reading or writing it. All system resources the file was using are freed up. No further methods can be called for the file.

We will present a complete list of the file operations in ` <chap4.html#22958>`__ of Chapter 4.

print() and printing¶

The print function 4 writes to the standard output. You can find

the standard output file object in the sys module, sys.stdout

print(e1, e2,...)

print(e1, e2,...,)

print(e1, e2,..., sep=separator_text)

The expressions are evaluated and converted into strings and written out with a blank between each pair. If the print statement does not end with a comma, the output line is terminated after the last expression is written (a newline character is written). If it does end in a comma, the line is not terminated, so the next print will continue to fill in the line.

The expressions are optional. You use a print with no expressions to write out a newline.

Note

Python 2 allowed printing to a file. This has been subsumed by writing

to a file. We recommend using the write() method on file objects to

achive this.

input() and raw_input()¶

Todo

Add these (soon).

while loops¶

while¶

The form of the while loop is

while expression :

indented body

The expression is evaluated to get a truth value. Python considers

zero to be false and any non-zero value to be true. It considers empty

strings (and other sequences) to be false, nonempty ones, true. If the

expression evaluates to true, the body of the loop is executed once and

the loop is restarted. As soon as the expression evaluates false, Python

stops evaluating the loop and goes on to the statement following it.

The statements in the body of the loop must be indented a uniform amount

of space beneath the while statement proper. Of course, if any of

the contained statements are while statements, their bodies must be

indented further.

Example: listfile¶

Here is an example of the use of a while statement in listing a text

file. If you want to follow along, you will need the Python interpreter

to be executing in the same directory as your code files. You can get

Python to your directory by

>>> import os

>>> os.chdir("directory")

in module os changes the current working directory. Now, suppose the

following code is in a file listfile.py :

def listfile(name):

f=open(name)

L=f.readline()

while L:

print(L,)

L=f.readline()

f.close()

We can import it and use it to list itself:

def listfile(name):

from listfile import listfile

listfile("listfile.py")

f=open(name)

L=f.readline()

while L :

print(L,)

L=f.readline()

f.close()

The code should be pretty obvious except for two points.

while L:Python considers an empty string to be false and a nonempty string to be true. That makes this loop easy, since end-of-file results inreadline()returning an empty string. In general, structured objects can sometimes be considered equivalent to zero for logical tests. We’ll try to point out these cases as we discuss them. Here, while we are discussing logical operators, we will just say zero and non-zero, or false and true, and not keep repeating that some things other than the number zero are also considered to be false.print(L,)The final comma prevents Python from inserting a newline following the string that has been written. Since the lines returned byreadline()all are terminated by newlines anyway, they come out single-spaced. If the comma weren’t there, the lines would come out double-spaced.

Relational Expressions¶

Theh expressions in while statements most commonly use relational

operators to compare operands. The result of a relational operation is

Boolean: True or False.

>>> 1 < 2

True

>>> 1 > 2

False

Unlike most other languages, Python allows relational operators to be cascaded:

>>> -2 < -1 < 0

True

>>> (-2 < -1) < 0

False

The first of the two expressions is equivalent to

-2 < -1 and -1 < 0. Python duplicates the value between the two

operators and does both comparisons separately. In the second

expression, (-2 < -1) yields True , then True<0 yields

False as True is promoted to 1 for the purpose of an

integer comparison.

If you find any of this confusing, just remember that True and False can be converted as neeeded to 1 and 0, respectively. You can use these values almost anywhere an integer is expected. Try this:

>>> False + False

0

>>> False + True

1

>>> True + True

2

>>> True - False

1

>>> True - True

0

Logical Expressions¶

Python provides the usual three logical operators, or, and, and

not, at the low precedence levels, 1, 2, and 3. See

tabletab:logical-operators.

x or y–The lowest precedence Python operator isor. The expressionx or yis short-circuited: It will not evaluateyifxdetermines the value of the expression. It first evaluatesxand returns the value ofxifxis not considered false. Ifxcounts as false,2 it evaluates and returns the value ofy. So the true value it may return is either the value ofxor the value ofy.x and y–Theandoperator, likeor, is short-circuited: It will not evaluateyifxdetermines the value of the expression. It first evaluatesxand returnsxifxcounts as false. Ifxis true, it evaluates and returns the value ofy. That has the effect of returning zero if eitherxoryis zero. If neitherxnoryis zero, it returns the value ofyto represent true.not x–Thenotoperator, at precedence level 3, although a unary operator, has a much lower precedence than the other unary operators at precedence 12. In fact, it is a lot more useful at a low precedence level. If it had a high precedence level, we would usually have to put parentheses around its operand. It returns 1 ifxis zero; it returns 0 ifxis anything else.

Lists¶

Lists in Python are like arrays in other languages. Actually, they are flex arrays, arrays whose size can change during program execution.

Lists can be created with a display. Just list the values between opening and closing brackets:

\(\lbrack e_0, e_1, \ldots, e_{n-1} \rbrack\)

A list of length n is created. The expressions \(e_0\),

\(e_1\), …\(e_{n-1}\) are evaluated and their values placed in

the list.

In addition, Python (2 and beyond) has a moresophisticated form of

display, the list comprehension. We will discuss it later, after we’ve

discussed the for and if statements it is based on.

Like arrays, lists can be subscripted by following the list’s name with the index of the item in brackets, thus

python3

Python 3.7.0 (default, Jun 28 2018, 13:15:42)

[GCC 7.2.0] :: Anaconda, Inc. on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> L=["a", "b", "c"]

>>> L[1]

'b'

>>> L[0]

'a'

>>> L[2]

'c'

>>> L[3]

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

IndexError: list index out of range

>>>

The positions in the list are numbered from zero, left to right. You can also assign to positions in a list

>>> L[1] = 1

>>> L

['a', 1, 'c']

Notice that the items in a list do not need to be of the same data type. Python lists, like variables, are typeless. Also notice that Python is able to write out an entire list when you ask for it, certainly more convenient than the arrays in some languages that you have to write out in a loop.

You can check the length of a list with the len() function:

>>> len(L)

3

Often you will need a list with successive integers in it. Python has a

built-in function, range() , to give that to you.

>>> range(10)

range(0, 10)

>>> list(range(10))

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

>>> range(-10, 0)

range(-10, 0)

>>> list(range(-10,0))

[-10, -9, -8, -7, -6, -5, -4, -3, -2, -1]

Calling range(i, j) gives you an iterator of integers from i up

to, but not including, j. Call range(n) is the same as

range(0,n). Why “up to, but not including”? It is compatible with

the indexing of lists, where a list of length n has indices 0 through

n-1.

Beginning with Python 3, range(i, j) is not evaluated until

necessary. To get a list of values, you need to use the list() to

demand the values from the iterator.

You can also create a list of values some step size apart, not just

sequential, by specifying the step size as the third argument to

range() :

>>> list(range(0, 10, 2))

[0, 2, 4, 6, 8]

If you are using lists as arrays, you obviously have to be able to create a list of some length. The length you need may be computed as the program runs, so you obviously can’t always use a list display. How do you create a list of length n?

You use the replication operator, *. Of course, this is the same as

the multiplication operator. If one operand of the * operator is a

list, L, and the other is a number, n , then L*n concatenates

n copies of L together.

>>> L

['a', 1, 'c']

>>> L*3

['a', 1, 'c', 'a', 1, 'c', 'a', 1, 'c']

>>> 2*L

['a', 1, 'c', 'a', 1, 'c']

A way to allocate an array of length 10 is

>>> ary=[0]*10

>>> ary

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

You can concatenate two lists by using the + operator:

>>> L+["d","e"]

['a', 1, 'c', 'd', 'e']

You can compare two lists for identity or for equality. The is

operator compares two objects to see if they are identical, i.e., really

the same object. The == operator compares objects for equality. Two

lists are considered equal if their contents are equal. The equality

test can be a lot slower than the identity test.

>>> [1,2] is [1,2]

False

These two displays create separate lists, so is returns false, but

the two lists are equal:

>>> [1,2] == [1,2]

True

Other relational operators work on lists as well. They operate lexicographically. The comparison works left to right through the lists, comparing the elements at the same positions, until it finds elements that are unequal, whereupon it uses the relationship of those elements as the relationship of the lists, for example

>>> [1,2,3] < [1,4,3]

True

>>> [1,2,3] < [1,0,3]

False

There are two special operators to test for list membership: x in y

reports true if x is in the list y and false otherwise;

x not in y reports just the opposite.

>>> 2 in [1,2,3]

True

>>> 2 not in [1,2,3]

False

You can get a copy of a part of a list using slicing. Slicing is like subscripting, but it specifies a range of indices.

r=range(10)

>>> r = range(10)

>>> list(r)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

>>> r = list(r)

>>> r[3]

3

>>> r[3:4]

[3]

>>> r[3:6]

[3, 4, 5]

>>> r[3:1]

[]

Notice a few things:

Subscripting,

r[3], returns the object that is at that position.Slicing, e.g.,

r[3:4], returns a list.The slice extends from thestarting index up to,

but not including, the ending index.If the ending index of a slice is less than or equal to the starting index, slicing returns the empty list.

You can use negative indices to indicate positions from the end of the list:

>>> r = list(range(10))

>>> r[-1]

9

>>> r[-10]

0

>>> r[-3:-1]

[7, 8]

If you leave out the start or the end positions when specifying a slice, they default to the beginning or the end of the list:

>>> r[:5]

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

>>> r[5:]

[5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

>>> r[:]

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

The r[:] may seem pointless, but it is a way to make a copy of a

list. This can also be achieved with list(r).

Consider the following.

>>> r = list(range(10))

>>> s = r[:]

>>> s == r

True

>>> s is r

False

>>> t = list(r)

>>> t == r

True

>>> t is r

False

In this example, we use the two different ways of copying list r as

s and t. Observe that in both cases, the resulting copy

compares equal but is clearly a different list object.

You can assign to a slice of a list by specifying the slice on the left- hand side of an assignment and a list on the right-hand side.

>>> L

['a', 'c']

>>> L[1:1]=['b']

>>> L

['a', 'b', 'c']

>>> L[0:2]=L[1:3]

>>> L

['b', 'c', 'c']

Assigning to a slice gives you a way of deleting elements:

>>> r = list(range(10)) >>> r[3:5] = [] >>> r [0, 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

You can also delete an item from a listusing the del statement:

>>> r = list(range(10))

>>> del(r[3])

>>> r

[0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

>>>

>>> l = list(range(10))

>>> del(r[3:5])

>>> r

[0, 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 9]

List objects have a number of methods you can call, as shown in the table List Methods.

They fall into several groups.

Two of the methods add elements to the list. Method call L.append(x)

adds an element x to the end of the list L (the new highest

position). Method call L.insert(i,x) inserts an element x at any

position i in the list L. All elements previously at that

position or beyond are moved up one position. The index i can be at

the end of the list, whereupon insert() behaves like append().

Method |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Places |

|

Places the list of elements |

|

Inserts item |

|

Removes and returns an item from the list. If an index, |

|

Removes the first item in |

|

Counts the number of items in |

|

Returns the index of the first item in |

|

Reverses the order of the elements of the list |

|

Sorts the elements of the list |

Method call L.remove(x) finds the first (lowest indexed) occurrence

of x in list L and removes it. All elements with higher indices

are moved down one. If you know the position, i , of the element you

wish to remove, use del L[i]. If you want to examine the item at a

particular position and remove it, use L.pop(i). If you want to

examine the last item and remove it, use L.pop().

To use L as a stack, use L.append(x) to push x on the stack,

and x=L.pop() to pop it off. To use L as a queue, use

L.append(x) to enqueue x and x=L.pop(0) to dequeue it.

Two methods examine the list for elements equal to a particular value.

Call L.count(x) returns a count of the number of occurrences of

value x in list L. Call L.index(x) returns the position of

the first occurrence of x in L. Remember, the expressions x

in L and x not in L test to see if the list L contains

element x.

Two methods permute the order of the elements of the list, in place.

L.reverse() reverses the order of the elements of the list L.

L.sort() sorts the elements of L into nondecreasing order.

Example: Self-Organizing List

In a self-organizing list, you move items that are accessed to the front so you can find them more quickly in subsequent searches. Here’s how you could implement self-organizing lists using list methods:

>>> def reorder(L, x):

... L.remove(x)

... L.insert(0, x)

...

>>> r = list(range(10))

>>> reorder(r, 5)

>>> r

[5, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9]

Example: Median Value of a List of Numbers

The median number in a list is the middle number in the sorted list, if there is an odd number of items. If there is an even number, the median is the average of the two middle numbers. Here is a function to compute the median:

>>> def median(L):

... s = L[:]

... s.sort()

... n = len(s)

... return (s[n//2]+s[(n-1)//2])/2.0

There are a couple of things to note about this code:

Rather than modify the array,

L, we make a copy before sorting it.Whether the number,

n, of elements is even or odd, we compute the median by averaging the elements at positionsn//2and(n-1)//2. This gives the correct answer in either case.

for loops¶

In Python, loops exist to allow an index variable to take on each

element in a list, or other sequence (iterable) object. (We’ll discuss

other sequences below.) The form of a for loop is:

for var in sequence:

body statement

...

body statement

Probably the most common form of for loop is

for i in range(len(L)):

# do something with L[i]

where i takes on the index of each item in the list, L. If you

only need to examine the items in the list but do not need to know their

positions, you can use the loop:

for item in L:

# do something with each item in L

continue Statement¶

If you decide that you are finished with the current iteration of a loop, you can execute the continue statement. It consists of the single word

continue

It will immediately end the current iteration and jump back to the top of the loop and start the next iteration. If there are no more iterations to do, of course, it falls out of the loop.

One major use for the continue statement is to filter the items in

the loop. Suppose we wish to print only those strings in a list that are

at least five letters long; we might do it as follows:

>>> x = ["book","placid","right","table","mother","gone"]

>>> for s in x:

... if len(s) <= 5:

... continue

... print(s)

...

placid

mother

We’ll eventually see how many for loops can be replaced with filters and lambda expressions. For now, here is the equivalent formulation where we iterate over a filtered result:

>>> for result in filter(lambda s: len(s) > 5, x):

... print(result)

...

placid

mother

break and else in loops¶

Often you will use a loop to search for something. Once you’ve found it, you want to escape from the loop. If you don’t find it, you often need to take some default action. Python makes it easy to do both of these.

If in the midst of a loop you wish to stop iterating, you can execute

the break statement. It consists of the keyword break :

break

If you want to execute some code if the loop terminated normally, i.e.,

if it didn’t exit by a break , you can attach an else clause on

the end of the loop. Loops with else clauses have the form:

while expr :

indented loop body containing break

else :

indented code to execute

if the loop exits normally

or

for var in sequence:

indented loop body containing break

else:

indented code to execute

if the loop exits normally

Of course the keyword else is usually used in if statements. It

is in Python too. It is perhaps not the best word to express the concept

of on normal termination, but it is what Python uses.

if-else¶

statement will execute code based on whether an expression is true. The

form of an if statement is

if expr:

indented code to be executed if expr is true

If you want to execute other code if the expression is false, use the

else clause:

if expr:

indented code to be executed if expr is true

else:

indented code to be executed if expr is false

elif¶

Of course, you often want to test a sequence of conditions and execute

code for the first one that’s true. Because of indentation, it would be

annoying if you had to put another if within the else and indent

further. Python avoids this problem with the elif clause, equaling

an else plus an if. The general syntax of an if statement

is:

if expr1:

indented code to be executed if expr1 is true

elif expr2:

indented code to be executed if expr1 is false and expr2 is true

else:

indented code to be executed if all exprs are false

Here would be an appropriate place to mention that Python does not have

a switch statement (as found in C language).

Switch statements choose one out of several blocks

of statements to execute based on the value of a single expression. You

will probably use an if statement with a sequence of elif

clauses for that purpose. (What else could you use? Well, you could put

functions into a list, index into the list, and execute one of them, but

that’s a lot of trouble.)

pass and One-Line Code Blocks¶

and elif clauses are executed in order until one evaluates true; the

block of code associated with that expression is executed and then

control passes to the statement following the if statement. This

means that the earlier expressions must test for more specific cases; if

you test for the more general case first, you will never get to the code

for the subcase.

But what if the desired behavior for the more specific case is to do

nothing? You need a statement that doesn’t do anything. In Python this

is the pass statement, which consists wholly of the keyword pass

:

pass

statement is only useful as a complete code block, and it is short.

Giving it an entire indented line to itself makes programs longer. That

may force related code to extend beyond a page or a computer screen. So

Python allows one statement block of code to be placed on the same line

as the statement that selects it. Just write the statement following the

colon of the if , elif , else , while , for ,

def (or of any other statement that ends in a colon introducing a

block of code).

Indeed, you can put several simple statements following a colon just by placing semicolons between them.

A tuple is an immutable list: It is just like a list except that you can’t change the contents. You create a tuple by a display consisting of expressions in parentheses separated by commas, for example:

>>> (1,2)

(1, 2)

Notice that Python writes out a tuple in the parenthesized notation.

The one place where parentheses become ambiguous is in constructing a tuple of length one. In that case, if you want a tuple of length one, put a comma following the expression, just before the final parenthesis. If you only intend a parenthesized expression, do not put in a comma.

>>> (1,)

(1,)

>>> (1)

1

You can have tuples with no components. Just use parentheses without anything between them:

>>> ()

()

You can subscript and slice tuples just like lists, pulling out elements or creating a copy of a section of a tuple. You cannot, however, assign to an element or a slice of a tuple; you can’t use the subscript or the slice operator on the left-hand side of an assignment. You can’t use the delete statement on a part of a tuple.

>>> q=(1,2)

>>> q

(1, 2)

>>> del q[0]

Traceback (innermost last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

TypeError: object doesn't support item deletion

>>> del q[0:1]

Traceback (innermost last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

TypeError: object doesn't support slice deletion

>>> q[1]=3

Traceback (innermost last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

TypeError: object doesn't support item assignment

>>> q[0:1]=()

Traceback (innermost last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

TypeError: object doesn't support slice assignment

You can concatenate tuples and replicate them, just like lists, using

the + and * operators. These operators produce new tuples; they

don’t modify an already existing tuple.

>>> (1,2)+(3,4)

(1, 2, 3, 4)

>>> (1,2)*2

(1, 2, 1, 2)

You can convert a tuple to a list using the list() built-in function

and a list to a tuple using the tuple() built-in function:

>>> list( (1,2,3) )

[1, 2, 3]

>>> tuple(range(3))

(0, 1, 2)

If you are constructing a tuple of at least one element on the right- hand side of an assignment statement, you don’t have to surround the expressions in parentheses. If it is to be of length one, you do have to be sure to put in a trailing comma:

>>> x=1,2,3

>>> x

(1, 2, 3)

>>> x=1,

>>> x

(1,)

statements. You can return a tuple from a function, and you can

construct the tuple in the return statement without enclosing it in

parentheses, unless of course it is length zero.

You can compare two tuples for identity or for equality. The is

operator compares two objects to see if they are identical. The ==

operator compares objects for equality. Two tuples are considered equal

if their contents are equal.

>>> (1,2) is (1,2)

False

(1,2) == (1,2)

True

These two displays create separate tuples, so is returns false, but

they have the same contents, so == returns true.

Todo

Rewrite for Python 3 world only.

test in Python1 uses a simple recursive search to test for equality. If

you have a circularly linked structure, e.g., a tuple containing a list

that is embedded within itself, the == operator may crash your

program. You cannot, however, embed a tuple within itself directly,

since it cannot be modified once it is created. It would already have to

exist before it is created to be made a component of itself.

The relational operators that compare lists compare tuples the same way:

>>> (1,2,3) < (1,0,3)

False

>>> (1,2,3) < (1,4,3)

True

>>> 2 not in (1,2,3)

False

>>> 2 in (1,2,3)

True

List Comprehensions¶

A list comprehension has the form index in range optional-for-and-if-clauses]

For example,

>>> [(x,y,x+y) for x in range(5) if x%2!=0 for y in range(5) if y!=x]

(1, 0, 1), (1, 2, 3), (1, 3, 4), (1, 4, 5), (3, 0, 3), (3, 1, 4), (3, 2, 5), (3, 4, 7)]

The behavior is as if you initialized an empty list and then appended

the expression to it in nested for and if statements. For

example:

[(x,y,x*y) for x in range(10) if x%2!=0 for y in range(10) if y!=x]

is roughly equivalent to

L = []

for x in range(10):

for y in range(10):

if x%2!=0 and y!=x:

L.append((x,y,x*y))

is now the list to use.

If you use a tuple as the expression in the list comprehension, you must put parentheses around it.

Dictionary Comprehensions¶

Python also supports dictionary comprehensions:

>>> { chr(x + ord('A')) : ord('A') + x for x in range(0, 26) }

{'A': 65, 'B': 66, 'C': 67, 'D': 68, 'E': 69, 'F': 70, 'G': 71, 'H': 72, 'I': 73, 'J': 74, 'K': 75, 'L': 76, 'M': 77, 'N': 78, 'O': 79, 'P': 80, 'Q': 81, 'R': 82, 'S': 83, 'T': 84, 'U': 85, 'V': 86, 'W': 87, 'X': 88, 'Y': 89, 'Z': 90}

The behavior is as if you initialized an empty dictionary and inserted

the expression to it in the for statement.

The dictionary comprehension above generates a dictionary of the ASCII values for the English letters ‘A’ through ‘Z’.

Note

Do not assume the keys of this dictionary will be in order. Dictionaries make no guarantees about ordering of the keys.

This code is roughly equivalent to the following:

D = {}

for x in range(0, 26):

D[chr(x + ord('A'))] = ord('A') + x

None¶

Lists and tuples, because they can contain references to other objects, allow you to build linked list data structures. For example, some languages (starting with Lisp) have built lists out of “cons cells” containing two references to other objects. These two references are sometimes called the head and tail of the list: The head is the first item, the tail is the rest of the list. (In Lisp they’re called the CAR and the CDR.)

You could have much the same effect by using two element tuples with the

head being at index zero and the tail being at index one. The problem,

though, is that you need some way to indicate the end of a list. Lisp

uses NIL. In C it’s usually called NULL ; in Java, null.

Python provides the value None. You might create a linked list

(1 2 3) as follows:

>>> x=(1,(2,(3,None)))

>>> x

(1, (2, (3, None)))

is as a placeholder. If you assign a variable the value None , the

variable will exist, but the value None can indicate that it hasn’t

had its value computed yet. The program can test to see if it has a

value without having to test first whether it exists. Trying to access

it if it doesn’t exist causes a runtime error, as shown here:

>>> x = None

>>> x == None

True

>>> del(x)

>>> x

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'x' is not defined

More on Assignment¶

Now we will consider assignment statements more closely. There are five things that need to be considered:

Multiple assignments of the same value

Unpacking sequences, assigning components of sequences to different variables at the same time

Operate-and-becomes assignments in Python, e.g. +=

The order of evaluation in assignment statements

Where variables are bound

We will consider these in order.

Multiple Assignments¶

First, you can include several assignments in the same statement. The form is

= expressions

This will assign the variables in the targets the value(s) of the expressions. For example:

>>> i = j =0

>>> i

0

>>> j

0

Both i and j are set zero.

Unpacking Sequences¶

Second, as we have already seen, more than one value may be assigned at the same time by separating the values with commas, for example:

>>> j,m = 0,1

>>> j

0

>>> m

1

This can be used to swap values

a, b = b, a

And multiple assignment and unpacking sequences can be used together, albeit somewhat confusingly:

>>> i,m = j,n = 0,1

>>> i,j,m,n

(0, 0, 1, 1)

You can assign from any sequence type, as long as the length of the variable list is the same as the length of the sequence. Lists, tuples, and strings are sequences, so

>>> i,j = (3,4)

>>> i,j

(3, 4)

>>> i,j=[5,6]

>>> i,j

(5, 6)

>>> i,j="ab"

>> i,j

('a', 'b')

Moreover, you can include subsequences on the left-hand side of the assignment, enclosing the list of variables in parentheses or brackets, thus:

>>> i,(j,[m,n]) = x = [1,[2,(3,4)]]

>>> i,j,m,n,x

(1, 2, 3, 4, [1, [2, (3, 4)]])

>>> i,j,m,n

(1, 2, 3, 4)

>>> x

[1, [2, (3, 4)]]

Notice that if there are several assignments in the statement, each one is matched separately to the value of the right-hand side. The different targets don’t have to look alike. Notice also that the parentheses and brackets on the left-hand side of the assignments do not have to correspond to tuples and lists respectively on the right-hand side.

As with tuples, a parenthesized variable is treated as a simple variable, but including a comma after it causes it to be matched to the contents of a single element sequence, as shown in the following:

>>> (x)=[9]

>>> x

[9]

>>> (x,)=[9]

>>> x

9

Operate and Becomes¶

Python allows certain binary operators to be combined with the

assignment operator. The general rule is that x op= y is equivalent

to x = x op y.

So, x+=1 is x = x + 1.

The operators that you can combine with an assignment are:

The arithmetic operators:

+,-,\*,/,%, and**The bitwise operators:

&,|, and^The shift operators:

<<and>>

Evaluation Order¶

The evaluation of an assignment statement evaluates the expression(s) on the right-hand side first, then assigns the resulting value to each of the targets from left to right. Within the targets, it also goes left to right making assignments. This can produce some confusion. Consider the following code:

>>> r = list(range(10))

>>> r.reverse()

>>> r

[9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]

>>> i=2

>>> i,r[i] = r[i],i

>>> r

[9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0]

has an initial value of two, you would expect that the assignment

...,r[i]=...,i

to r[2] , replacing 7 with 2 in the sequence. But before

that happens, we assign

i,...=r[i],...

which is to say, we assign i=r[2] , or the value 7. Then we assign

r[7] the value 2 , which was already there.

Assignment to Local Scope¶

When Python performs an assignment, it assigns to the variable in the

innermost scope. If it is executing a function (within a def ), the

variable will only be seen by code in that function and will exist only

as long as the function is executing. If the assignment is at the top

level of a module, i.e., in a file but not inside a def or class

statement (we’ll talk about classes later), then the variable will be

known in the module and will exist as long as the program is

running–unless you explicitly delete it.

global Statement

So what if you want to assign a value to a module-scope variable in a

function? You can’t just assign a value to the variable name; that would

create a local variable with the same name. What you can do is use the

only declaration in the Python language, the global statement. The

global statement has the form global id1, id2, ....

It declares that the variable names id1 , id2 , etc. are

variables of the surrounding module and are to be fetched and assigned

there. The global statement must appear before the variables are

used.

Deleting Variables

You create a variable in a scope just by assigning to it. You can delete

it from the scope using the del statement.

>>> x=9

>>> x

9

>>> 9

9

>>> del x

>>> x

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

NameError: name 'x' is not defined

Dictionaries¶

A dictionary is a mutable, associative structure. Considering these characteristics one at a time:

Mutable: You can add key-value pairs to a dictionary and remove them.

Associaive: Dictionaries map keys into values. Given a key, you can look up its value. It looks like indexing a list or tuple, but unlike lists and tuples, the keys can be almost any immutable data type, not just integers. (It is peferrable that keys be immutable because if you put the key in the table and then changed its contents, you might not be able to look it up again.)

Dictionaries are like small, in-memory databases. The table Dictionary Methods shows the operators, functions, and methods available for dictionaries.

Operator, Function, Method |

Explanation |

|---|---|

|

Creates a dictionary with the given key-value pairs. |

|

Returns the value associated with key |

|

Associates value |

|

Deletes key |

|

Removes all key-value pairs from dictionary |

|

Creates a copy of the dictionary |

|

Returns the value associated with key |

|

Returns the value associated with key |

|

Returns True if dictionary |

|

Returns |

|

Returns a list of all the keys currently in dictionary |

|

Adds all the key-value pairs from dictionary |

|

Returns a list of all the values currently in dictionary |

|

This method is a bit strangely named, because its end result is to set and then get a value from the dictionary. Its behavior is to test whether a key |

You can create an empty dictionary by writing an open-close-brace pair:

>>> d={}

>>> d

{}

You can create a dictionary with initial contents by placing one or more associations in the braces:

>>> d={"a":1,1:(2,3),(2,3):"a"}

>>> d

{(2, 3): 'a', 1: (2, 3), 'a': 1}

In this example, we associate the string key "a" with the value 1;

key 1 with the value tuple (2,3) ; and the key tuple (2,3)

with the string value "a." (They don’t have to form a cycle like

this.)

You can look up the value for a key by subscripting the dictionary with the value of the key.

>>> d[1]

(2, 3)

>>> d[(2,3)]

'a'

Since Python uses the equality operator, == , to test the keys,

equal numbers are considered to be the same key:

>>> d[1.0]

(2, 3)

Be careful, though, with floating point numbers. They are not exact, and they may differ by a few bits in the low order positions even if they look equal.

It is a runtime error to look up a nonexistent key in a dictionary.

>>> d[10]

Traceback (innermost last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in ?

KeyError: 10

If you don’t want to worry about an error when looking up a value, you

can use the get() method. The call d.get(k) will yield the value

for key k in dictionary d , if it exists, or return the value

None if it doesn’t. The call d.get(k,v) is the same, except that

it returns the value v if the key isn’t present.

>>> d

{(2, 3): 'a', 1: (2, 3), 'a': 1}

>>> d.get(10)

>>> d.get(10) == None

True

>>> d.get(10,"absent")

'absent'

Notice that the Python interpreter doesn’t write out the value None

in interactive mode.

Alternatively, you can ask whether the dictionary contains the key

before subscripting with it. Method call k in d will return

true or false (1 or 0) depending on whether the dictionary d

contains the key k or not. (Operator in does not apply to

dictionaries.)

>>> 1 in d

True

>>> 10 in d

False

You can insert a new key-value pair into the dictionary by subscripting a dictionary on the left-hand side of an assignment operator with the key and assigning it the value. You can assign a new value to a key the same way:

>>> d[10]=10

>>> d

{(2, 3): 'a', 10: 10, 1: (2, 3), 'a': 1}

>>> d[10]="a"

>>> d

{(2, 3): 'a', 10: 'a', 1: (2, 3), 'a': 1}

The len() function will tell you the number of associations the dictionary contains:

>>> d

{(2, 3): 'a', 10: 'a', 1: (2, 3), 'a': 1}

>>> len(d)

4

You can use the del statement, del d[k] , to remove

association k from the dictionary d.

>>> del d[10]

>>> len(d)

3

>>> d

{1: (2, 3), (2, 3): 'a', 'a': 1}

Note

Never depend on the ordering of keys in a dictionary. Dictionary key ordering may differ from what you see in any of our examples.

There are three methods to examine the contents of a dictionary without knowing the keys:

Call

d.keys()to iterate of all of the keys currently in the dictionary.Call

d.values()to iterate all of all the values.Call

d.items()to iterate all of the key-value pairs ind.

The key-value pairs are in ( key,value ) tuples.

>>> d

{1: (2, 3), (2, 3): 'a', 'a': 1}

>>> d.keys()

dict_keys([1, (2, 3), 'a'])

>>> d.values()

dict_values([(2, 3), 'a', 1])

>>> d.items()

dict_items([(1, (2, 3)), ((2, 3), 'a'), ('a', 1)])

To create a copy of a dictionary, you could create an empty dictionary and then update it from the one you want to copy, for example:

>>> e={}

>>> e.update(d)

>>> e

{1: (2, 3), (2, 3): 'a', 'a': 1}

behaves the same as:

>>> e = {}

>>> for k in d.keys():

... e[k] = d[k]

...

>>> e

{1: (2, 3), (2, 3): 'a', 'a': 1}

But it is easier, more efficient, and less error-prone to use the copy() method:

>>> e = d.copy()

When you copy a dictionary, you get a shallow copy. The dictionary object is copied, but none of the keys or values it contains are. Consider the following example:

>>> x = { "a" : [0] }

>>> y = x.copy()

>>> x is y

False

>>> y["a"][0]=1

>>> x

{ "a" : [1] }

The value associated with key "a" in dictionary x is a list

containing a single value, zero. When we copy x , we get a new,

different dictionary, y. Dictionaries x and y are not the

same, but the lists they contain are, so when we change the list

associated with key "a" in dictionary y , that is the same list

we see associated with ” a ” in dictionary x.

Relational operators other than == do not work on dictionaries the same way as sequences as of Python 3,

presumably because it is computationally expensive. It would also not be meaningful when the

dictionaries have different sets of keys.

If you wanted to compare dictionaries, you would need to obtain a representation that is sorted by key. In the following, the two dictionaries are converted to lists of tuples, sorted, and compared.

>>> D1={ "x" : 1, "y" : 2, "z" : 3 }

>>> D2={ "x" : 1, "y" : 4, "z" : 3 }

>>> D1==D2

False

>>> L1 = list(D1.items())

>>> L2 = list(D2.items())

>>> L1.sort()

>>> L2.sort()

>>> L1

[('x', 1), ('y', 2), ('z', 3)]

>>> L2

[('x', 1), ('y', 4), ('z', 3)]

>>> L1 < L2

True

>>> L1 > L2

False

Strings¶

Strings are a kind of immutable sequence, like tuples. Once the string has been created, you can’t change its contents. Unlike tuples, where the elements of the sequence may be of any data type, the elements of a string are characters. You can subscript a string, but you don’t get an individual character. Python has no character data type. You get a string of length one containing the character.

The original strings in Python contained byte-sized, Latin character set/ASCII characters. Python also provides Unicode character strings. We will assume the original character set in our discussion except where we explicitly discuss Unicode.

String Literals¶

There are several ways to write string literals. If you are going to

write the string on a single line, you can enclose it in single quotes (

' ), or double quotes ( " ). This easily allows you to enclose a

string containing one kind of quote inside the other kind of quotes, for

example:

>>> 'He said, "Hi."'

'He said, "Hi."'

If you need both kind of quotes, you can write more than one string in a row and let Python concatenate them for you. Here we use three strings in a row:

>>> 'He said, "She said,' "'Hi.'" '"'

'He said, "She said,\'Hi.\'"'

The output here shows Python’s incorporation character, the backslash. The backslash tells Python that the following character is to have a special interpretation within the string. Python’s incorporation sequences are shown in the following table Incorporation Character Sequences in String Literals.

Sequence |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

Continues the string literal to the next line, without including a newline character |

|

Includes a backslash character |

|

Includes a single quote |

|

Includes a double quote |

|

Includes an attention signal (beep) character |

|

Includes a backspace character |

|

Includes an escape character |

|

Includes a form feed character |

|

Includes a line feed (newline) character |

|

Includes a tab character |

|

Includes a carriage return character |

|

Includes a vertical tab character |

|

Includes a null character. (Unlike C, Python allows null characters in strings.) |

|

Includes the character whose octal code is |

|

Includes the character whose hexadecimal code is |

|

Only in Unicode strings, incorporates the character whose hexadecimal number in the Unicode character set is |

Suppose you need a string to extend beyond the end of a line. There several ways to do it. You can get Python to continue the statement on the next line and put quoted parts of the string on the separate lines. Since Python understands that unbalanced parentheses require continuing the statement to another line, this will work:

>>> ("a"

... "B")

'aB'

Python will also continue a statement if the last character on the line is a backslash.

>>> "a"\

... "B"

'aB'

For that matter, a backslash also works within strings:

>>> "a\

... B"

'aB'

Python also allows strings to be enclosed in triple quotes, either

""" or '''. These strings may extend beyond the end of a line

without special handling. However, they include a newline character

(\n) for each line boundary they cross:

>>> """a

... B"""

'a\nB'

If you do not want a newline character included for the end of a line, put a backslash character at the end of the line:

>>> """a\

... B"""

'aB'

Python also allows you to specify raw strings. In a raw string, you get the characters exactly as written. The incorporation character has no special meaning. This is more useful to people using Windows, since backslash is used to separate directories and files on paths (those found in the DOS/Windows world in particular), and it would be annoying to have to incorporate each one of them:

>>> r"D:\Tests\SayHi.py"

'D:\\Tests\\SayHi.py'

One warning: A backslash may not be the last character of a raw string. Python tries to gobble up the following character as part of the string.

You write Unicode string literals by preceding the string with u ,

e.g., u'ab\u12adyz'. If you concatenate two string literals, one of

which is Unicode, the Python compiler merges them into a single Unicode

string.

String Operators¶

The string operators are the same as those that apply to tuples, with one extra operator for string formatting. The operators are shown in the table String Operators.

Operator |

Meaning |

|---|---|

|

Produces a new string which is the concatenation of strings |

|

Creates a new string composed of |

|

String formatting–Creates a new string by formatting values in tuple |

|

String formatting–Creates a new string by formatting values in dictionary |

|

Yields a one-character string composed of the character at position |

|

Yields a string composed of the characters from position |

|

Converts the value of expression |

|

Assigns one-character substrings of string |

String Evaluation

The equivalent of [...] for lists and (...) for tuples is eval(...)

for strings. The form eval(x) evaluates expression x and converts

its value to a string, for example:

>>> a=1;b=2

>>> eval("a+b")

3

>>> eval("(a,b)")

'(1, 2)'

Sequence Operators

Strings are a kind of sequence, so the sequence operators apply to

strings. Expression u+v will concatenate strings u and v.

Expression s*n will concatenate n copies of string s.

Slicing will deliver a substring. Expression s[i:j] yields a string

composed of the characters from position i up to but not including

position j in string s.

Unlike lists and tuples, subscripting, s[i] , cannot deliver an

individual character. Python does not have characters. Instead, it

returns a string consisting of the one character at position i.

Expression s[i] is equivalent to s[i:i+1].

String Formatting

String formatting behaves like the formatting strings used in the

printf() function in C. String formatting is specified by the

s%t operator in Python. The string s to the left of the % is

the format. The tuple or dictionary to the right of the % supplies

the values to be formatted. Generally, characters in the format string

are just copied as is into the result string, but certain special

character sequences are replaced with values from the tuple or

dictionary. Since tuples and dictionaries behave differently, we will

discuss the tuples first and then explain the differences with

dictionaries.

The formatting sequences are matched left to right with the values in the tuple. Each formatting sequence specifies how to convert the value to a string. The converted value is then inserted into the resulting string, replacing its formatting sequence. For example, the following produces a string with the number 65 translated into octal, decimal, and hexadecimal, the translations separated by colons:

>>> "%o:%d:%x" % (65,65,65)

'101:65:41'

If there is only one value to be formatted, you needn’t include it in a tuple, for example:

>>> "|%d|" % 5`

|5|

The formatting sequences have the form:

% m f

The modifiers, are optional. The formatting character, f , tells Python (internally, the C library) what conversion to perform. The formatting

characters are

d- Decimal integer. The corresponding element of the tuple is converted to an integer and the integer is converted to a string in decimal format.i- Decimal integer. The same as%d.u- Unsigned integer. The same as%d, but the integer is interpreted as unsigned. The sign bit is interpreted as adding a large positive amount to the number, rather than a large negative amount.o- Octal integer. The corresponding element of the tuple is converted to an integer and the integer is converted to a string in octal format.x- Hexadecimal integer. The corresponding element of the tuple is converted to an integer and the integer is converted to a string in hexadecimal format. Lowercasexuses lowercase letters for the digits 10 through 15.

>>> "%x" % (-2)

'fffffffe'

X- Hexadecimal integer. The corresponding element of the tuple is converted to an integer and the integer is converted to a string in hexadecimal format. UppercaseXuses uppercase letters for the digits 10 through 15.

>>> "%X" % (-2)

'FFFFFFFE'

f- Floating point format, with decimal point but without an exponent.

>>> "%f" % (0.5e-100)

'0.000000'

e- Floating point format, with decimal point and an exponent (with a lowercasee).

>>> "%e" % (0.5e-100)

'5.000000e-101'

E- Floating point format, with decimal point and an exponent (with an uppercaseE).

>>> ``"%E" % (0.5e-100)``

'5.000000E-101'

g- Choose eitherfore,depending on the size of the exponent.G- Choose eitherforE,depending on the size of the exponent.s- String, or any object being converted to a string.>>> "%s" % ([1,2]) '[1, 2]'

r- Like s, but usesrepr()rather thanstr()to convert the argument.c- A single character. The value to be converted can either be an integer that is the internal code for a character or a string of length one.

>>> "%c" % (88)

'X'

>>> "%c" % ("Y")

'Y'

%- This does not match an element from the tuple. It is the way to incorporate a percent sign into the string.

The modifiers, if present, have the form

a w.p

each of which is optional. These parts are as follows:

a- The alignment; can be a plus sign, a minus sign, or 0, or some combination of them. They mean the following:-- Align the characters at the left in the field+- Include a sign for numeric values, even if positive. (Normally only a negative sign would be included.)0- Zero-fill the number in the field.

w- The width; specifies the minimum field width the formatted value is to occupy. This allows nicely aligned output, at least with fixed-width fonts, if the values fit within the field width specified. If they don’t fit, they will use all the character positions required.

>>> "|%4d|" % 5

'| 4]'

>>> "|%4d|" % 500000

'|500000|'

p- The precision; follows a decimal point. It has one of three meanings:For strings, the precision specifies the maximum number of characters that may be printed from the string.

>>> "|%.3s|" % ("abcdef") '|abc|'

For floating point numbers, it specifies the maximum number of digits following the decimal point.

>>> "|%.4f|" % (1.0/3.0) '|0.3333|'

For integers, the precision specifies the minimum number of digits to represent.

>>> "%4.2d" % 5 '| 05|'

If you want to compute the width or precision, you can use stars, *

s, in width or precision fields. The star tells Python to use the next

item in the tuple, which must be an integer, as the value in the field,

for example:

>>> "|%*.*d|" % (4,2,5)

'| 05|'

You can use a dictionary instead of a tuple. You instruct Python what

value to format by putting the key string in parentheses just after the

opening % , inside the formatting sequence:

>>> "|%(x)4.2d|" % {"x":5}

'| 05|'

However, this doesn’t work for the formatting fields:

>>> "|%(x)4.(p)d|" % {"p":2,"x":5}

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

ValueError: unsupported format character '(' (0x28) at index 7

The String Module and String Methods¶

The string module provides a number of useful functions and constants. In Python, functions from the string module were made into methods of string objects. The tables Most Important String Operators and Methods and Most Important String Operators and Methods (Continued) shows the most useful of these functions and methods.

String Module |

Method |

Explanation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Find the index of the first occurrence of |

|

|

Find the index of the first occurrence of |

|

|

Find the index of the last occurrence of |

|

|

Find the index of the last occurrence of |

|

|

Return a list of the substrings of |

|

|

Concatenate the strings in list or tuple |

String Module |

Method |

Explanation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Return a copy of |

|

|

Return a copy of |

|

|

Return a copy of |

|

|

Return a copy of |

|

True if |

Built-In String Functions¶

Python features some built-in functions not addressed in the preceding discussion.

chr(i)- Returns the character (in a one-character string), whose ASCII code is integeri. This is equivalent to("%c" % i).ord(c)- Returns the ASCII code ofceval(s)- Evaluates the stringsas if it were a Python expression.>>> eval("[1,2]") [1, 2]

You can also give

eval()dictionaries to look up variables in:eval(s,globals)or``eval(s, globals, locals)``:>>> eval("x+y",{"x":1,"y":2},{"x":3}) 5

hex(i) - Returns a string representation of integer ``iconverted to hexadecimal representation.>>> hex(65) '0x41'

It is not equivalent to

("%x" % i), which does not put"0x"on the front.int(s)- Converts a string to an integer. (It will also convert long integers and floating point numbers to integers.)oct(i)- Converts integerito a string representation of it as an unsigned octal integer.>>> ``oct(65)`` '0101' >>> oct(-1) '037777777777'

ord(c)- Returns the integer representing the single character in stringc.repr(x)- Returns a string representation of objectxthat could be passed toeval(e).str(s) - Returns a string representation of object ``x. Unlikerepr(),str()does not attempt to be the inverse ofeval(). It attempts to make the translated string legible.

- 1

This chapter is adapted from Thiruvathukal, Christopher, and Shafaee, Web Programming in Python, 2002. Rights have been reverted to the authors for this out-of-print work. It is also being updated for Python 3, which is what we use exclusively in this book.

- 2

Python is easy to run on Linux, OS X, and Windows. For Windows, we recommend installing Windows Subsystem for Linux to get a complete Linux shell environment. To be covered in preliminaries section.

- 3

Python also provides full UNICODE support.

- 4

Earlier Python versions feature a

printstatement, which allows you to write code without calling a function. This is no longer supported in Python 3.